Humans are the missing link between natural and social sciences

In Emilia-Romagna in Italy there was a lot of pressure and stress on agricultural land, as it was increasingly used to cultivate energy crops. Local inhabitants and environmental organizations were able to mobilize alternative knowledge concerning biogas production. This resulted in a policy shift, politicians gradually became more open to listen to local feedback. Illustration photo from the Emilia-Romagna region, by Pixabay.

Solutions for the transition to become a sustainable society are often high-tech, take biofuel plants as an example. Fancy technology, political strategies and economic support schemes are, however, useless if humans are not able to adapt and cooperate across sectors.

It’s called sustainability transitions. Humans, their cognitive and social interactions, are key factors to understand if we aim to support changes towards sustainability. However, they are often the missing link between natural and social sciences.

“From a social science perspective, what we do is to study and understand how people perceive the environment, the technologies, the ecosystems, and the new tools they are going to adopt,” says Bianca Cavicchi. She recently finished her PhD in Bioeconomy Transitions Policy Analysis.

“One key question we, as social scientists, are often asked by our fellow natural scientists is why farmers and forest owners don’t follow their advices. I believe that behind this question there is a call for more transdisciplinary work across businesses, politics, and different research areas,” Cavicchi says.

She highlights that a combined natural and social science perspective could help in dealing with such challenges.

“Nowadays, that are methods, like system dynamics and life cycle thinking, that allow for this. We can reach a deeper understanding of the interaction between society and the ecosystem, and potentially be more successful at making natural resources management more sustainable”.

Transition to biofuels in Norway and Italy

In her PhD Cavicchi studied and compared the transition to biofuels in Hedmark region in Norway, and Emilia-Romagna region in Italy.

In short:

- How biofuel incentives were implemented and received in both areas.

- How local communities responded to actual or expected changes to the rural landscape and environment.

- How politicians responded to social opposition and problems along the way.

- Limitation to growth due to political adjustments and changes in market demands.

“My main focus was on bioenergy, but the analytical method can be applied to any bioeconomy transition process. The transition to a sustainable bioeconomy has to do with changes in technologies, production processes, organizational structures, mindsets, culture and ways of interacting within different societies.”

She explains that a different understanding of the relationship between humans and the natural environment is needed. Notably, the interdependence of communities´ perceptions and mental models of the natural environment, their actions and the ecosystem´s adjustments and reactions.

“I’ve tried to find the missing link between the socioeconomic and environmental processes. I focused on the process that leads to the creation of policies. I made a step backwards aiming to help the policy makers and decision makers to improve the decision processes,” Cavicchi says.

Italy: opposition to biofuel “gold rush” led to policy changes in favour of small-scale plants

New technologies may have an impact on people’s lives in several ways. In Emilia Romagna, local inhabitants and environmental organizations raised issues such as the lack of benefits provided to local agriculture and rural areas, and better environmental regulations. They requested the regional government to suspend the concessions to build new plants.

“In Emilia Romagna there was kind of a “gold rush” for the use of natural resources, such as land and biomass to produce biogas. The lack of trust in the political system and the lucrative financial support made investors go solo and prevented collaborative investments. The situation resulted in a lot of pressure and stress on agricultural land, as it was increasingly used to cultivate energy crops. Additionally, biogas plants were poorly managed, because many of the investors were not well prepared,” Cavicchi explains.

She found that local inhabitants and environmental organizations were able to mobilize alternative knowledge concerning biogas production. They started local actions to change how the bioenergy system worked, for instance through the submission of a Moratorium asking for regulatory changes to the regional government.

“What I saw in Italy was that the policy makers shifted from a defensive to a more open attitude. They became more open to listen to local feedback. The bioeconomy transition process wouldn’t stop, it just became a bit different.”

Because of the urgency of the protests, politicians were urged to respond to the problems.

“Politicians had to deal with the problems right away, otherwise it would have stopped the technological development of the regional bioenergy system. I mean, people would have had to stop investing and producing and so on.”

The fixes introduced by both national and regional decision makers slowed down investments in large biogas plants, but provided new opportunities for small-scale, waste and agriculture byproduct-based plants and biomethane production.

The way we look at, and deal with problems is crucial in order to achieve sustainable transitions.

“I’d like to highlight the necessity of a change in mindset. We should try to see the conflicts as opportunities, to learn from what people are telling us, to improve the policies, the way we do things and so on. In Emilia Romagna politicians learned from local actors´ what people were telling them, and they managed to redesign it in a way that wouldn’t stop the transition and the adoption of technologies. It made the process a little bit more environmentally sustainable and socially acceptable,” Cavicchi says.

Norway: Collaborative and sustainable forest investments, but weak connection to the industry

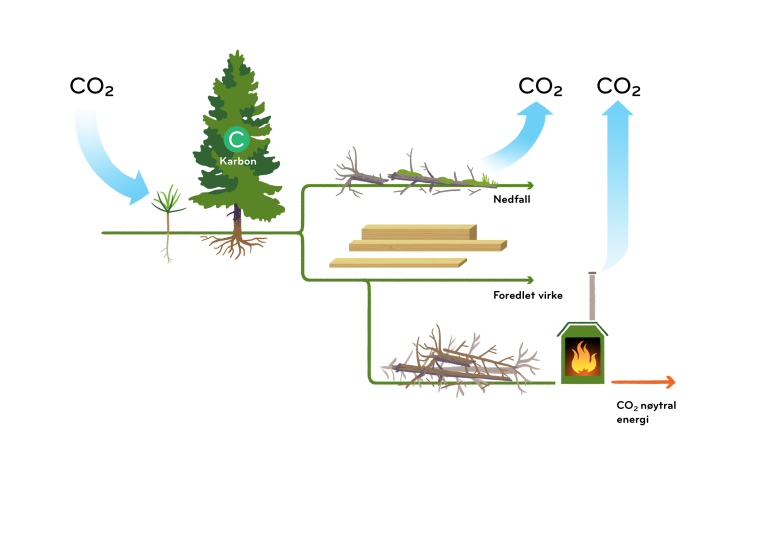

“In Norway there haven’t been strong conflicts. One reason may be that every year the growth of new forest exceeds the extraction of forest resources, and thus local communities have not perceived such a strong threat to the natural environment,” says Cavicchi.

She comprehends more trust between stakeholders in Norway.

“It makes a difference in the way people invest and do things, because if you trust each other, usually you are more willing to collaborate,” says Cavicchi.

She explains that in Norway bioenergy companies are usually created as a collaboration between different types of organisations, such as forest-owners, energy companies and public authorities.

Cavicchi states that there is also a different view of the natural environment in Norway, compared to Emilia-Romagna:

“In Norway the natural environment is an important asset for the local economy, people´s wellbeing, kids healthy growth and so on, thus people generally tend to want to preserve nature. In Emilia-Romagna, in the context of a highly industrialized region, the view of nature as an economic asset prevailed.”

She found that on the one hand, there is an embedded sense of trust in the Norwegian society, for example that bioenergy companies respect the natural environment. This sense of trust avoids strong social opposition. That being said, the dominance of hydropower keeps electricity prices low and makes it hard to compete in this market. «This has certainly been a key limiting factor to the diffusion of bioenergy in Norway,” Cavicchi says.

Integrated policies and strategies to cope with time delays

Territories have different capacities, resources, natural environments, climate conditions and needs. Cavicchi underlines that bioeconomy strategies must be adopted to the local conditions to achieve the transition sustainably and successfully. In order to succeed, there are especially two things she believes policy makers need to be aware of:

- The need to integrate different strategies and policies across sectors. Today we often see strategies with conflicting goals from different political departments.

- Today’s decisions may have an impact in the next 10, 50 or 200 years. Politicians need to plan for possible time delays when they make policies and strategies.

“As human beings we have a very short time perspective. But when you use natural resources and trigger biological processes in the environment, it takes time to display both positive and negative effects,” Cavicchi says.

Tekst frå www.nibio.no kan brukast med tilvising til opphavskjelda. Bilete på www.nibio.no kan ikkje brukast utan samtykke frå kommunikasjonseininga. NIBIO har ikkje ansvar for innhald på eksterne nettstader som det er lenka til.

_cropped.jpg?quality=60)