A nose for trouble – sniffing out plant pests

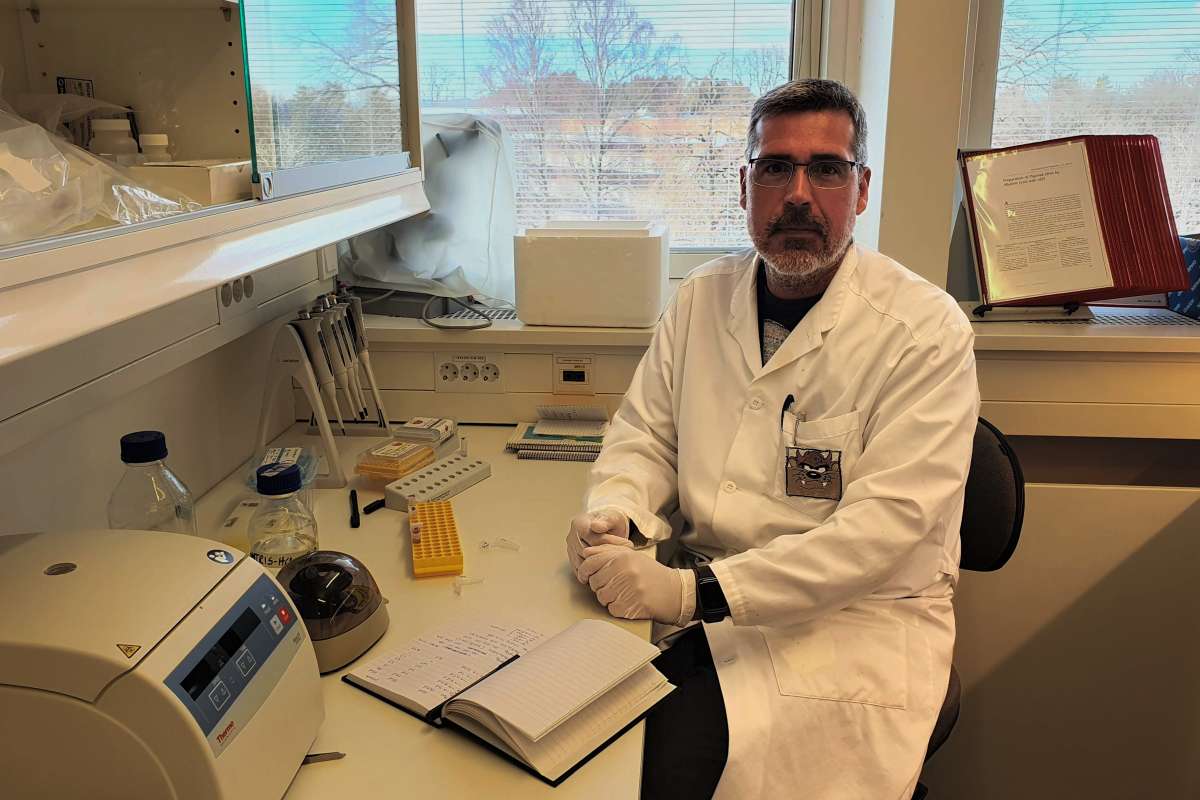

Researchers at NIBIO investigate imported plants at a plant nursery. Many plant pests are difficult to discover and are thus transported across borders as stowaways on plants or plant matter. Photo: Erling Fløistad

Invasive plant pests are threatening safe and sustainable food production. Many plant pests are transported across international borders on plants, where they can hide as stowaways. Researchers from all over Europe have joined forces to create electronic noses that can sniff out plants infected with certain pests, to prevent the pests from spreading.

Safe and sustainable food production is threatened by a variety of plant pests, many of them invasive. With a world population that is expected to reach 9.7 billion in 2050, according to the United Nations, we must prevent the loss of food and feed to pests and diseases.

Plant pests can be spread all over the world when plant material is traded. With climate change, the pests can establish in new areas and cause great economic losses. International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC), and European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) are both dedicated to protecting plants from pests, and work towards a safe plant trade to prevent the spread of invasive pests. However, this is challenging, as plant pests can be difficult to detect. When traded, plants are evaluated, and seemingly healthy plants get a plant health certificate. Unfortunately, many of these plants host hidden plant pest, which are then transported across borders as stowaway passengers. When they reach new destinations, they can spread rapidly and cause great damage.

This challenge has inspired researchers from all over Europe to cooperate in PurPest,an EU-project coordinated from NIBIO. The goal is to develop electronic noses that can sniff out stowaway pests in plants, and thus limit their distribution.

A nose for sick plants

Andrea Ficke, NIBIO researcher and project coordinator, explains the concept of the project:

“All plants secrete volatile organic compounds (VOCs), like smells. The collection of VOCs that a plant secretes is altered as the plant is subjected to stress, such as when under attack from a plant pest. Attacks from different pests should result in different VOC profiles.”

This principle will be used to create electronic noses, that can identify specific VOC profiles and connect them to certain plant pests. The electronic noses must be easy to use and give rapid and reliable results if it detects a pest.

This could prove to be a valuable tool for plant importers, that must manage large quantities of plants from all over the world, with currently few ways of detecting stowaway pests. According to Ficke, only 3% of the pests that are imported with plant material, are detected.

“By using electronic noses, it would be possible to detection rate to 80%.”

The electronic noses will be designed for in-field use as well. Robust electronic noses could be attached to tractors and used to detect pests that are already established in the fields. This would allow for more site-specific treatment, which could lower the need for pesticides with as much as 50%, Ficke claims.

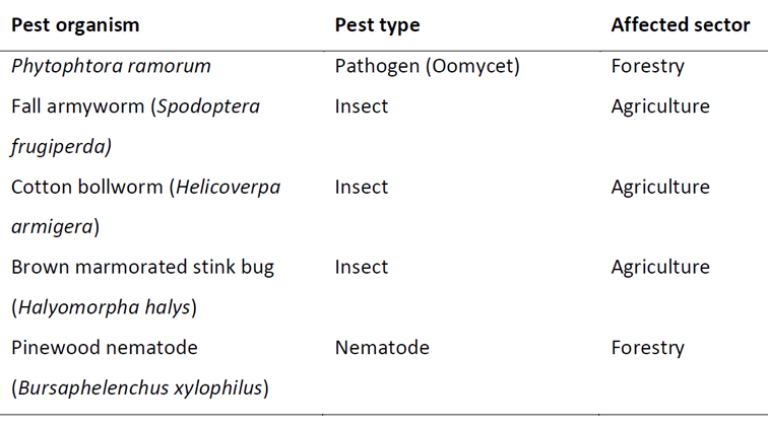

The select few

To start with, the project aims to develop electronic noses that can detect five pests, representing oomycetes, insects and nematodes. Most of the pests have a wide range of host plants and threaten both agriculture and forestry throughout Europe.

To be able to develop electronic noses, the volatile organic compounds secreted from plants attacked by different pests must be known. This will be achieved through controlled experiments conducted by NIBIO and other collaborating research institutes, where plants will be exposed to the different pests under controlled conditions. Analyses will be performed to determine the secreted VOCs, which will be gathered in a database. The database will be open to other researchers and developers, so that it can be expanded to be valid for other pests as well.

“This ensures that the technology and its uses can be developed, even after the project is concluded”, Ficke explains.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

Electronic noses alone will not solve the issue of invasive plant pests being imported with plants.

“To solve such a complex problem, we need changes in policies related to plant trade”, Ficke explains.

One of the projects’ working groups will work solely on this.

“They will work closely together with end users, such as farmers and people involved in plant trade, and stake holders, to create policies and guidelines that are sensible and implementable.”

This is an essential part of the project, which has set a goal to improve EU policies regarding plant trade. The cooperation between technology, biology and social sciences is essential for reducing the threat posed by invasive plant pests. By gathering expertise in these fields of research, the PurPest project can help secure sustainable food production and forestry.

Contacts

Phytophtora ramorum

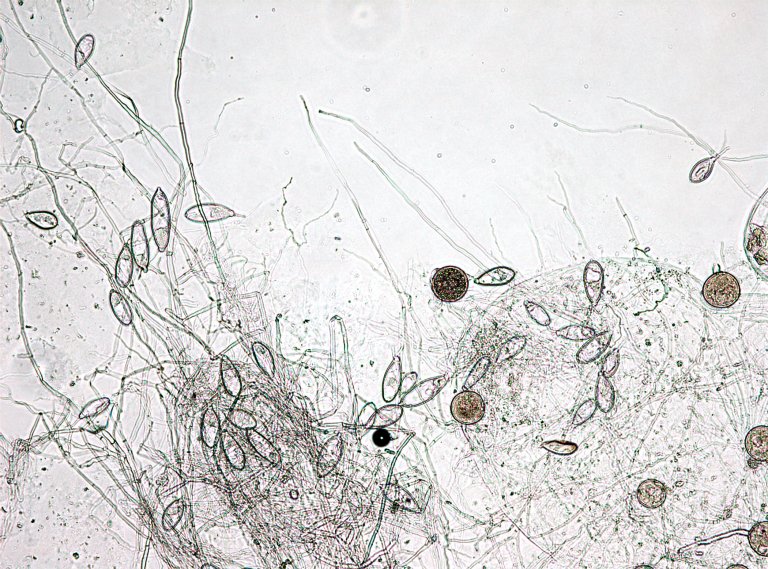

Phytophtora ramorum is a quarantine pathogen in Europe. The genus Phytophtora resembles fungi in many ways, but belongs to a separate kingdom in the tree of life, the Chromista kingdom. Phytophtora ramorum has more than 100 host plants and has caused the death of millions of oak trees in the US and larch threes in the UK. It is therefore known as Sudden Oak Death/Sudden Larch death. The pathogen is airborne and spreads naturally with spores by wind and rain splash. It also has a soilborne phase and spores can be transported far by waterways. However, longer distance spread is mainly through infected plant material. Phytophtora ramorum can survive as dormant spores in the soil and on dead plant material for several years, which makes it almost impossible to eradicate the disease from an infected area. Airborne spores infect above-ground plant parts and cause leaf or twig blight and bleeding stem cankers. Infections destroy the plant tissues and prohibit nutrient and water supply, leading to dieback and mortality.

Spores of Phytophtora ramorum grown in the lab. Photo: Erling Fløistad

Brown marmorated stink bug

The brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys) has more than 100 host species, mainly fruit trees, woody ornamentals and field crops. Both nymphs and adults feed on plant juices from leaves, stems and fruits. The bug flies from host plant to host plant, and is transported over long distances through plant trade. It is found in several countries in the southern parts of Europe.

Brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys). Photo: Erling Fløistad

Pinewood nematode

Pinewood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) can cause serious damage to pine trees. After infection, the tree can die within 1-2 months. The nematode is dispersed over short distances with the beetle Monochamus spp. Over long distances, the nematode is spread with infected wood material, or together with Monochamus larvae. Wooden material can be used in all sorts of trade, which increases the risk of spreading. In Europe, the pinewood nematode is found only in Portugal and Spain.

Pinewood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Photo: Erling Fløistad

Fall armyworm and cotton bollworm

Both fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) and cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) are moths that feed on several globally important crops such as maize and wheat (fall armyworm) and cotton, tomatoes and maize (cotton bollworm). Adult insects can migrate over long distances, and eggs and larvae can be transported with plant material. Cotton bollworm is found in the southern regions of Europe. Fall armyworm is not yet established in Europe, but has a high potential to spread worldwide and seriously threaten food security.

Contacts