When food runs short, moose suffer across generations

Moose in southern Scandinavia have become lighter and less productive over the past decades. Photo: Morten Günther

Moose in southern Scandinavia have become lighter and less productive over the past decades. In some areas, the decline in body condition has been dramatic. Climate, forestry, parasites, human activity, and a shortage of large bulls have all been suggested as explanations—but a new, comprehensive study from NIBIO shows that food availability remains a fundamental factor.

For more than 20 years, researchers have done extensive field surveys of moose forage resources from Agder county in the south to Trøndelag county further north in Norway. The result is one of Europe’s most detailed datasets on food availability, browsing pressure, and moose condition. Now, this material is beginning to provide clear patterns.

Forage surveys: What moose eat – and how much

Forage surveys are a method to measure how much food is available in the forest and how heavily it has been browsed. While traditional methods were designed for rapid monitoring of browsing pressure, the researchers in this study used a more detailed, research-focused approach:

“We measured the actual, absolute amount of forage, rather than using the more coarse, indirect indices commonly employed,” explains Hilde Karine Wam, research professor at NIBIO.

“We recorded the length of unbrowsed shoots in centimetres, giving a precise picture of available winter forage. We also mapped the coverage of all plant species, not just trees.”

The result is a comprehensive overview of moose food resources—both during the growing season and the “lean” winter months.

Food quantity matters – but not equally everywhere

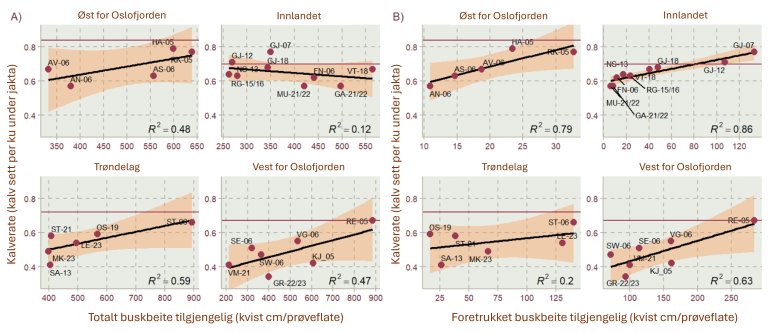

A key finding is a strong link between food availability and moose condition. Populations living in areas with abundant, varied forage have cows with higher calf ratios and better calf weights.

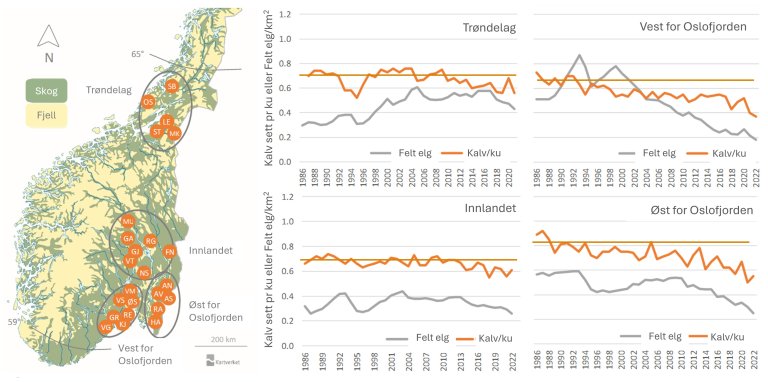

However, the picture is not uniform across the country. Natural factors such as snow depth, terrain, and bedrock influence the results. In some areas, moose must spend more energy to find food, while other areas offer greater diversity of forage plants. The researchers therefore divided the study areas into four regions with different potential for producing moose forage.

“The same amount of food does not necessarily result in the same condition in different parts of the country,” Wam explains.

The legacy of overbrowsing: When the past holds a grip on moose

One of the most interesting findings concerns “persistent maternal effects”: the impact of past overbrowsing passed down across generations.

Poor condition can be inherited. Cows that grow up with limited food become lighter as adults and produce fewer, smaller calves. This effect can persist for several generations—even if food availability later improves.

“In areas that have been heavily overbrowsed historically, moose are still lighter and less productive than expected based on today’s population density and food availability,” Wam says.

Researchers found this type of historical overbrowsing in large parts of southern Norway, especially west of the Oslofjord, where several populations showed clearly reduced condition compared to what would be expected from current forage levels.

Calf ratios reveal food shortages more clearly than calf weights

Another clear pattern is that the number of calves per cow is a more sensitive indicator of food shortage than calf weights.

“A cow in very poor condition tends to produce only one calf rather than two, which is more common in healthy cows,” explains Wam.

“The calf that is born may still achieve a reasonable weight because the mother draws on her own body reserves to nurture the calf. For this reason, calf ratios reveal problems with poor food availability sooner than calf weights do.”

Moose favourite forage can be decisive—but is often scarce

Birch is the most common browse tree in most study areas, but it is rarely a species selected for by moose, except in areas with few other deciduous trees.

“When moose can choose freely, they prefer rowan, aspen, willow, and oak,” Wam says.

The four species are called ROSE species, based on their Norwegian names.

Research shows that in most places; moose condition is more closely tied to the amount of these preferred tree species than to the total amount of available tree forage (often called browse). On average, ROSE species make up only about one-sixth of the tree forage.

“Moose achieve their best condition where they can afford to be selective,” Wam explains.

Large differences between regions

The amount and type of forage needed to maintain moose in good condition vary greatly geographically.

On the west side of the Oslofjord, a historically overbrowsed region, up to ten times more ROSE forage is required to reach the same moose condition as in, for example, Østfold county. In Innlandet county, which has the least historical overbrowsing, moose do well on relatively small amounts of high-quality forage.

In coastal Trøndelag county, total forage quantity, rather than ROSE forage, has limited moose condition, partly due to shorter winters and the greater importance of summer forage.

“Preferences for certain tree species matter mainly in winter. In summer, a birch can be as attractive as a willow,” Wam explains.

This study provides a rare opportunity to quantify how much high-quality food is needed—and where the greatest risk of deficit exists.

A new rule of thumb for management

One of the most useful findings for practical management concerns birch:

“Most moose populations seem to decline in condition when more than 15–20 percent of birch shoots are browsed in winter over time.”

This provides a clear threshold for monitoring moose forage. Birch is also a better indicator than rowan in many areas, as rowan is often so heavily browsed that it no longer reflects changes in browsing pressure.

Vital knowledge – even in a warming climate

“Although the study tells us what has worked so far, the future is more uncertain,” Wam says.

Climate change, increased land development, more human activity, altered forest management, and rising competition with other deer species will put further pressure on moose.

It will likely become harder for moose to maintain good condition in the coming years. Regardless, 20 years of forage surveys provide a solid knowledge base for more proactive moose management.

“Forage surveys can signal problems before the moose themselves show clear signs of declining condition,” concludes the researcher.

Contacts

What is a forage survey?

A forage survey is a systematic assessment of food conditions for large herbivores in an area, often used in forestry, outfield grazing, and deer management. Surveys help map the amount of available forage, the types of vegetation present, the impact of browsing on young trees, and how well the area meets the animals’ needs.

Contacts

Publications

Abstract

Cervid (Cervidae) populations that are overabundant with respect to their food resources are expected to show declining physiological and reproductive fitness. A proactive solution to such declines is to integrate the monitoring of food resources with animal harvesting strategies, but there are few studies available to guide managers regarding which food resources to monitor and how to do so. In this study, we used a large, rare data set that included detailed absolute measures of available food quantities and browsing intensity from field inventories, to test their relationship with fitness indices of moose Alces alces in 24 management units in four regions across Norway. We found that calf body mass and calves seen per cow during the autumn hunt were strongly and positively related to the availability of tree forage, especially the species most selected for by the study moose (e.g., rowan [ Sorbus aucuparia ] and sallow [ Salix caprea ]). The strength of the correlations varied between regions, apparently being stronger where the moose were closer to being overabundant or had a legacy of past overabundance. As expected, the intensity of browsing on the three most common tree species, that is, birch ( Betula spp.), rowan, and pine ( Pinus sylvestris ), was also negatively and strongly related to the fitness. We discuss how our approach to food monitoring can facilitate a management that proactively adjusts densities of moose, and possibly other cervids, to trends in food availability and browsing intensity, thereby avoiding detrimental effects of overabundance.