Automated hunt for nocturnal moths

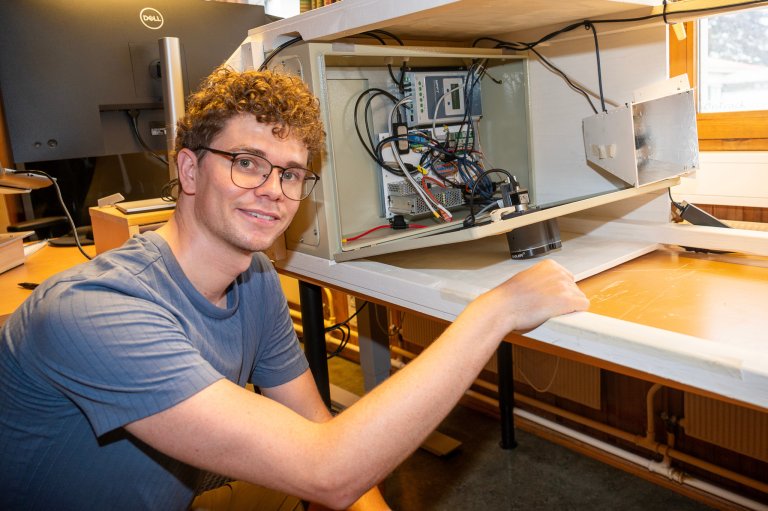

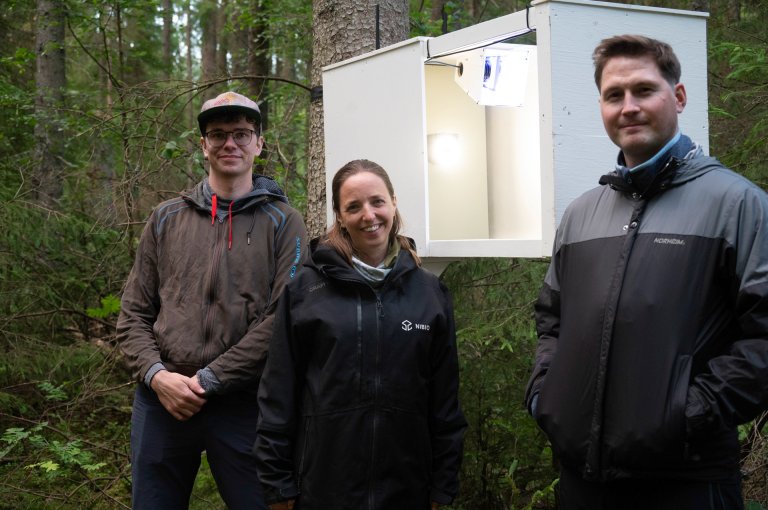

The new light trap will take photos that can be analysed using artificial intelligence. This can provide researchers with valuable insight into which species of moths are present, when they are active, and to what extent. Photo: Morten Günther

As is often the case, the large and beautiful tend to get the most attention. That’s why we know very little about many of our small moth species. Now, researchers at Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO) want to use new technology to gain more knowledge about this large group of fascinating insects.

In Norway, there are more than 2,300 species of butterflies and moths. You may know some of the large, colourful butterflies like the common brimstone, peacock butterfly, mourning cloak, or Old world swallowtail. But did you know that 95% of our butterflies and moths are small, camouflaged, and active at night?

“Nocturnal moths are a group that has received little attention, and their importance is understudied, perhaps precisely because they are active at night,” says researcher Fride Høistad Schei at NIBIO. Her specialty is biodiversity in forests.

“Many nocturnal moths are important pollinators. We believe they play a more significant role in forest pollination than previously realized.”

New tools – new opportunities

Digital tools offer researchers new opportunities to map and monitor nature. In a new project, NIBIO is focusing on these nocturnal and little-known moths.

Together with entomologist Jørund Johansen and robotics engineer Steffan Lloyd, both also at NIBIO, Fride Høistad Schei has developed a new digital light trap. The researchers were inspired by a Danish study, but the new trap is more advanced and has the potential to identify far more species.

The goal is for the light trap to take photos that can be analysed using artificial intelligence. This can provide valuable insight into which species are present, when they are active, and in what numbers.

MothWatcher

It’s a bright summer evening in early June. In a forest area 60 km southeast of Oslo, the three NIBIO researchers are assembling the automatic light trap for the first time.

The light trap, named “MothWatcher,” consists of a wooden box with a built-in camera, flash, and a special LepiLED lamp. This LED light source emits UV, blue, green, and white light to attract moths and other nocturnal insects. It uses the same type of light as traditional traps. But unlike traditional traps, which collect insects in a container, this digital trap does not capture them. If they land on the white light plate, a photo is taken, but they can fly off at will.

The camera takes a picture of the white surface every five seconds during a preset time period. The light is only on at night, so the trap only attracts insects when it's dark.

Using artificial intelligence

The researchers also use AI to identify the individuals in the images.

“There are several reasons why artificial intelligence is well-suited for identifying nocturnal moths,” says Jørund Johansen.

“Many species have distinct wing patterns that allow for identification from images. The light behind a white surface encourages moths to remain still longer, which improves image quality. The white background provides a uniform surface, making it easier to distinguish individuals than if the background were natural vegetation.”

“The light trap is powered by a large battery connected to a solar panel. It charges during the day when the trap isn’t in use and has a 4G internet connection for remote monitoring in the field,” Lloyd explains.

Large amounts of data collected

Last season served mostly as a test phase. Would the technology work in the field? Would the images be good enough?

After nearly a year, they are now seeing the results, and the researchers are satisfied so far. The light trap was deployed from June to November. The material hasn’t been fully analysed yet, but spot checks show over a thousand insect images.

“We experimented with different light settings and background placements. We will continue to adjust to improve image quality,” says Lloyd.

However, last year’s data collection was affected by power availability. Norwegian summers aren’t always sunny, and extended bad weather reduced the power supply. This year, the light trap will be placed near a power source, and the researchers may upgrade with more solar panels.

“We were concerned birds might see the trap as a snack bar. So, we avoided using the attractive light during dusk and dawn when birds are very active. Fortunately, we got no photos of hungry birds,” says Høistad Schei.

Developing a new and improved system

“By combining NIBIO’s expertise in technology, AI, and biodiversity, we are working on developing MothWatcher 2.0,” says Høistad Schei.

“We will also continue working with the material we already have and with new data collected this year. We want to find out if this technology can be used in future monitoring efforts.”

So far, the researchers have used species recognition algorithms from the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre (Artsdatabanken). This open service already provides good identification.

However, the NIBIO researchers want to develop their own AI tools and hope to get some students involved.

“Our goal is to create our own identification algorithms. That will require a lot of work. Among other things, we need many images to train the AI,” says Høistad Schei.

“We also want to compare our data with results from traditional light traps. They might catch different species, but I don’t really see why that should be the case,” says the NIBIO researcher.

Increased focus on technology-based knowledge development

The three NIBIO researchers are committed to strengthening the institute’s focus on data-driven and technology-based knowledge development.

“It’s very exciting to work across disciplines and explore the possibilities for monitoring biodiversity using new technology,” says Høistad Schei.

“Such systems can generate valuable knowledge useful for understanding and managing biodiversity. Since all data are verifiable, this also provides us with an efficient and standardized monitoring system,” concludes the researcher.

Contacts

Nocturnal moths

In Norway, about 2,300 species of moths and butterflies have been recorded. Around 100 of these are butterflies, while the remaining 2,200 are moths.

Nocturnal moths are not a systematic insect group, but rather a common term for those active at night.

Our nocturnal moths include families such as hawk moths, lappet moths, owlet moths, tortrix moths, true moths, and geometrid moths.

Contacts